Nuclear weapons ban comes into force – without peace nation Norway

On January 22nd. nuclear weapons became forbidden under international law. “This is a historic milestone and an important piece of international legislation. Now the long-term work of achieving a world without nuclear weapons can really begin,” says senior advisor on mine- and weapons policy, Grethe Østern.

Text: Sissel Fantoft

The ban on nuclear weapons has been ratified of 51 UN member countries and is supported by 87 others. Norway is not one of them.

“Now we have both a legal and political tool with which we can measure progress towards a world without nuclear weapons. Experience tells us how the prohibition treaty comes first, followed by the long-term work of elimination afterwards,” says Østern.

Countries that support the agreement undertake never to develop, produce, test, possess or store nuclear weapons. The agreement also prohibits any transfer or use of nuclear weapons or the threat of the use of such weapons.

“The first step is to bring about acceptance of the agreement, then to get more countries to sign up to it. Then the implementation phase can begin,” she says.

The world’s nine nuclear powers (USA, Russia, the UK, France, China, India, Pakistan, Israel and North Korea) boycotted the negotiations when the ban was adopted, as did the 32 so-called umbrella states – countries whose security is based on protection from nuclear weapons. Norway is one of these countries.

“Opposition is common where such treaties are concerned; it took, for example, several decades before China and France joined the nuclear non-proliferation treaty which was negotiated in 1968. The nuclear weapons ban challenges those countries whose policies are inconsistent where nuclear weapons are concerned: they express support of nuclear disarmament but do not distance themselves from nuclear weapons in practice. They continue to encourage allied nuclear weapons states to maintain their nuclear weapons, and potentially use them, on their behalf,” says Østern.

8 out of 10 support a ban, and 90% of these people think Norway should sign the agreement. The government is thus wholly at odds with popular opinion.

From accepted to taboo

Norwegian People’s Aid has conducted three surveys among Norwegians concerning the ban on nuclear weapons.

“8 out of 10 support a ban, and 90% of these people think Norway should sign the agreement. The government is thus wholly at odds with popular opinion. The ban means that Norway’s stance is brought to the surface and will thus be more widely debated,” says Østern.

She believes that the ban raises a number of challenging issues for the authorities.

“We see that a number of politicians are trying to undermine the agreement. This is clear evidence that they feel challenged by it. Very important decisions are to be made and the way we talk about nuclear weapons will gradually change on account of the ban. From being accepted, nuclear weapons will become taboo, and this also needs to be recognised by a humanitarian powerhouse such as Norway,” she says.

Østern is convinced that the ban will lead to greater global efforts to engage the nuclear powers in real negotiations.

“Sooner or later the umbrella states and nuclear powers will sign up to the ban. This is the only international agreement that contains requirements for total nuclear disarmament, and that such disarmament is verified,” she says.

In a year’s time, the state parties and observers are set to meet in Austria to take important decisions about the way forward.

“This is the germ of a disarmament regime that does not exist today. The agreement provides a framework for establishing such a regime so that it is already in place on the day when one or more nuclear powers decide to join. Whether disarmament takes place inside or outside of the prohibition treaty does not matter, the point is that we get there,” she says.

Nuclear weapons are not only appalling in principle but also senseless

A driving force for negotiations

Last year, 56 former prime ministers, foreign ministers, and defense ministers signed an international appeal to world governments to sign the treaty banning nuclear weapons. Among them was former Prime Minister Kjell Magne Bondevik.

“I admit that some years ago I thought such a treaty would not make much difference one way or the other but now I have come to a different conclusion. I believe that this agreement can be a tool to increase opposition to nuclear weapons, and help achieve the long-term goal of a world free of nuclear weapons,” he says.

The reason for this, he believes, is that nuclear weapons are not only appalling in principle but also senseless.

“I have asked myself the question: Do we in Norway want to be defended by nuclear weapons? My answer is no. We know that if nuclear weapons are first used by one country, it is likely to escalate rapidly and total catastrophe and annihilation will result. We simply have to work against this,” says Bondevik.

He believes that the convention can be a driving force to kick-start negotiations between the nuclear powers.

“There may well be parallel negotiations between the United States, France, and the UK in the West with Russia and China across the table. Perhaps we can also try to initiate negotiation processes between India and Pakistan, where there is considerable tension today. I am also thinking about Israel and Iran, which may be on the way to becoming a nuclear power, and North Korea, with which the United States and South Korea primarily must negotiate,” he says.

Independent stand

Bondevik hopes that the Norwegian authorities also consider signing the agreement.

“I am aware that they are under great pressure from NATO and the nuclear powers, but there is nothing in international law to prevent us from signing such a convention. It is of course politically problematic, but sometimes Norway must be willing to take an independent stand, even though I know from experience that it is not easy,” says Bondevik.

He underlines that the former ministers who have signed the appeal are far from naïve idealists.

“We have all had a great responsibility for security policy in our respective countries, but I believe that the time has now come to rethink. We must try to remove the risk that nuclear weapons represent, especially since such weapons have fallen into even more hands,” says Kjell Magne Bondevik.

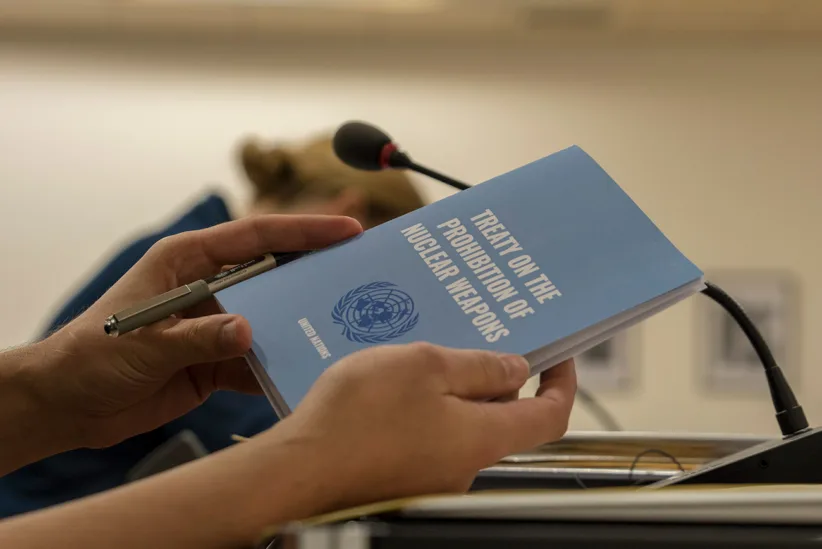

This is the first international agreement to prohibit the development, testing, and use of nuclear weapons

In 2017, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) received the Nobel Peace Prize for ‘its work to draw attention to the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons and its ground-breaking efforts to achieve a treaty-based prohibition of such weapons’.

“It will be a historic moment when the agreement enters into force today. It is the result of decades of work, from when the first survivors after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki began to fight against the use of nuclear weapons, until today,” says policy and research manager Alicia Sanders-Zakre in ICAN.

Huge recognition

From this day on, all the countries that have signed up to the agreement are legally bound to comply with its provisions.

“This is the first international agreement to prohibit the development, testing, and use of nuclear weapons. Signatory countries also undertake to offer assistance to victims of nuclear weapons testing and to restore areas that have been contaminated by such testing. It is truly groundbreaking and remarkable,” says Sanders-Zakre.

She believes that the agreement will also strengthen the stigma related to nuclear weapons.

“In the same way as with previous weapons bans, we expect that this agreement will influence countries that have not yet signed so that more will eventually join. The countries that have nuclear weapons will be out of step with the global norm,” she says.

The Nobel Peace Prize was a huge recognition of ICAN's work, and at the same time created awareness around the issue.

“The prize has helped put a spotlight on the importance of peaceful, global solutions,” says Alicia Sanders-Zakre.